1. Your work often varies between the traditional poem utilizing line breaks and stanzas and he prose poem, which focuses more on the use of the sentence. What guides you in choosing the format for the piece? You seem to write more in prose format. You’ve called yourself a hybrid poet. Can you explain what that means to those who may be unfamiliar with the concept?

DD: When I know what I am setting out to say, I tend to write in prose or narrative (sentences with line breaks). I may not wind up saying what I thought I was going to say, but if I do have a “story” of some sort, that’s the way it goes. There are many kinds of prose poems, including meditative, surrealist, fabulist etc. I like the form because it is so inclusive. If I am in more unfamiliar territory, subject-wise (that is, what seems to me unfamiliar), I like to work in forms, traditional and those I make up. In other words, I give myself a project.

2. Who are some of your favorite non-Anglo American writers?

DD: Marjorie Agosin, Pablo Neruda, Ocatavio Paz, Ioana Ieronim, Wisława Szymborska

Any new writers that you are watching to see where they go?

DD: Stacey Waite is absolutely fantastic! She has a couple of chapbooks out and I can’t wait for her first book.

3. How does feminist criticism influence your poetry?

DD: Tremendously. I am a child of the Women’s Movement…It was actually COOL to be a feminist when I was in 6th grade—that is, in 1973. So I embrace the movement and read a lot of feminist criticism and theory.

To elaborate on this, you have called yourself a feminist poet. What does that mean to you?

DD: I want to make women the subjects, not the objects, of my poems.

4. A two-part question:

It has been said that you push the “proverbial envelope.” You yourself have said that you like to break taboos in your work. With strong feminine voices like yourself discussing the role of gender, sex, money, etc do you feel there are still taboos out there to be broken?

DD: Yes!

Funny females were once taboo, think Barbara Streisand in Funny Girl. But you have been called witty, freewheeling, a writer with zany humor. I personally have been brought to tears by your hilarious humor. Do you find the world of poetry less accepting of funny female writers than male writers? What do you feel is humor’s role in poetry today and to come?

DD: As an undergrad, I was told that only “ugly” women can be funny. That is, women who don’t fit into the dominant culture have more to work with. Think fat, loud, etc. When I was in my twenties, I was intimidated by that statement. I didn’t want to have to exaggerate what was “wrong” with me, what was culturally unacceptable. But now I think that idea is changing—with people like Chelsea Lately who fits the norm of who is “pretty” and also hilarious. I think she’s opened up who can get a laugh. In poetry, we are not “seen” exactly on the page. But still, I think the idea of humor’s role in poetry is quite large, especially in terms of socio-political poetry. Satire and absurdity are important.

5. Your poetry so often speaks to bigger picture discussions like in Kinky and the poems Hispanic Barbie and Black Barbie History, in $600,000 from Ka-Ching!, and Why on a Bad Day I can Relate to the Manatee. Do you consider yourself a political poet? What do you see as poetry’s role in American politics, in creating change in American society?

DD: Yes. I do see myself as a political poet. Why not? I think poets should write about everything they want to write about. I think poetry is about making readers see the world differently and opening it up. Having said that, I don’t have an inflated idea of what poetry can “do.” I’m a realist.

6. Your work is candidly honest from relationship poems in Star Spangled Banner and especially in Ka-Ching where you discuss the tragic accident your parents were involved in when an escalator collapsed in 2003. I believe this seemingly open access into your life is why your work is so easy for readers to connect to. What influenced you to be so open with your readers especially in a world today when we are encouraged to be distant in order to protect ourselves?

DD: I was open and honest in my work from the beginning because, in all seriousness, I never thought anyone would really read it. I certainly never thought I’d be published. So now that people have read what I’ve written and no one throws tomatoes or boos, I feel emboldened to continue on that path.

7. In your interview with Karla Huston you discussed that at one point you had to get away from the “I poems.” In much of your latest book, Ka-Ching!, you revert back to the “I perspective.” What brought you back to this “personal narrative” as you called it like that in Smile and Star Spangled Banner?

DD: It was simply time, I think. I don’t think one way of writing is better than the other. I think it’s just a process—you reach the end of one road and turn down another. Then you make two lefts and you are back where you started.

8. After you received your MFA at Sarah Lawrence you have said that you decided that you were “in poetry” for the long haul. Do you think you will ever stop writing? What keeps you going?

DD: I love writing—I love the act of sitting down with a pad of paper or a journal or a laptop. It’s a way for me to connect with myself and with the world. I’ll stop, I suppose when I’m dead. Unless the dead are able to write.

9. Many of your books have a theme to them like with Kinky being about Barbie, (which I love by the way), Ka-Ching! focusing on money and your parents’ accident. Do you find that this way of compiling a book makes it easier to focus on the material or does it jut happen that way because of whatever is going on in your life or society at the time?

DD: I write a lot of poems and when I put a book together, I look back and see the themes—or try to see the themes. I didn’t set out to write a book about money, but when putting together Ka-Ching! I could see that had been an obsession. I knew I was going to write a book of Barbie poems at some point—I guess when I had twenty or so and wanted to keep going.

10. Many of the blog’s readers are active writers always looking for new ways to find inspiration. As a teacher of poetry and a successful writer with 10 books under her belt, would you mind sharing one or more of your favorite exercises to get those juices flowing?

DD: Get your hands on a copy of Joe Brainard’s I Remember and write your own list of “I remembers….” It almost always works

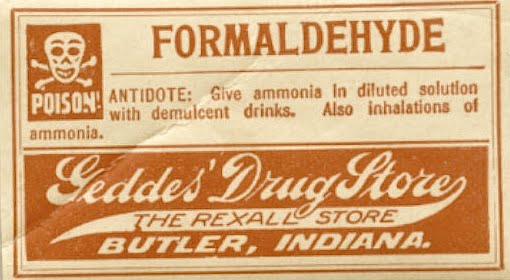

11. The final and toughest question: Would you mind sharing a poem or two with Formaldehyde’s readers?

DD: Sure! As you may know, I’m a big proponent of collaboration. Here is a poem my friend Haya Pomrenze http://www.hayapomrenze.com/author.php

and I just finished. Coincidentally, it’s called HYBRID.

HYBRID

The day we napped, I felt like a letter in an envelope—

an old-fashioned letter, pre text messages and the pillows

were not too hard, not too soft—just right.

The sleep lines on our faces made us look like lions

and tigers and bears chased our dreams

right through the snooze button. We woke up hungry,

clawed at the oranges we’d packed, the pith

of which reminded us of childhood when

it stuck in our teeth as we didn't know when to stop.

Oh bitter seeds of adulthood. We had two choices—

to believe in the tooth fairy and Santa

or Frank Sinatra and his throaty oath

though he wore a bowtie to hide his huge Adam's apple.

In kindergarten I relished naptime, the sticky plastic mat

smelled of juice, Crayolas and Sister Anne's breath.

In college your lumpy futon held you as you fantasized

about the Italian exchange student with suspenders, fiddled

with a yellow dildo you found on a rack at the Goodwill.

It was fruitless, reminding you of Ken who went

into the priesthood to avoid coming out. What I needed

was a guy who wrestled but romanced me with love letters

and garden vegetables he grew in his backyard. What did I know

then of ripe love, the kind when two people share a worn blanket

and post coital drool? You have slept in 276 beds (counting hotels)

and not once have you forgotten to say the Shema prayer, your hands

clicking rosary beads. You became to be a religious hybrid

when your housekeeper took you to Church of God on Palm Sunday, waving

her dusters like pompoms. In the pew, you read the forbidden missal

but there was no Amazing Grace or food after services.

I drew two triangles to make a Star of David, two lines to make a cross,

thought of Tiger Woods and his Buddhist roots.

Your paternal great-grandmother, you’re told, lived in Thailand

where she sold curried Challah, opened the first fusion

synagogue for Friday night meditation and matzo balls,

light as nirvana, personified. My maternal great-grandfather practiced voodoo

in Kenya poking dolls of his mother-in-law, a moled witch

known for her sour love potions of tree bark and umeboshi plums

she had long ago placed in her vagina for birth control.

The men in the village scorned her for her prunes of deceit, but the women

deified Mamachia. They came to her thatched home bearing gifts

of seashells that foretold the future. The women in our families have always napped,

with eyes wide open or wide shut. They summoned ancestral spirits

through feathers or foam, Craftmatic, Lazy Boys, hammocks—

their fingers brailing wisdom, like a Pillow Book.